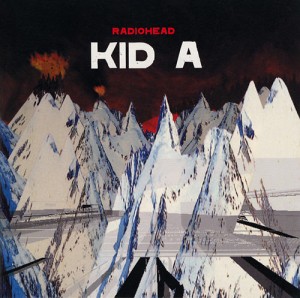

Radiohead

Kid A

October 2000

Capitol Records

Produced by Nigel Godrich

For a band so uninterested in the visual presentation of its members, and so stark in its stage performance, it is simply amazing how misunderstood Radiohead’s music is by both critics and fans. Books could be written on the history of misunderstandings between journalists and Radiohead, and on misleading marketing campaigns.

Radiohead are not balladeers of depression and apathy—not makers of “music to slit your wrists to”, as early critics had it—but authentic documentarians of dread and free-floating anxiety. Their vitality is sparked by outrage, even disgust, not rapture, at the insignificance of the inhabitants of contemporary democracies. Sure you can vote, but will your vote even be counted? Where to turn when your candidate or political party does not represent your views?

“I laugh until my head comes off” (from the masterpiece “Idioteque”) are the words of a man unhinged with bitterness and despair. This is the nanosecond before the bomb goes off. “Idioteque” is one of the most authentically frightening songs of recent years: if the university-educated, politically-engaged Radiohead of Oxford can’t see a way out, then maybe we really are in irretrievable trouble. (“Morning Bell” isn’t much less spooky, with singer and lyricist Thom Yorke chanting ‘walking, walking, walking’ in the background and sounding like Jack Nicholson in The Shining.)

“Idioteque” also seems to satirize the worst failure of the other greatest band in the world: U2 and their ghastly, pointless “Discotheque” from the Pop album (1997). Maybe Radiohead aren’t so oblivious to competition as they let on?

“Ice age coming/ women and children first/ We’re not scaremongering/ this is really happening”. No kidding, pal. Yorke has an astonishing capacity for telescoping a series of thoughts, whether a wad of newspaper editorials or an avalanche of scholarship. “Ice age coming/let me hear both sides” drops out the central referent (the debate between the GOP versus the rest of the educated world about the existence of global warming) while remaining entirely comprehensible.

Sure, Yorke will toss in the odd bizarro word (“Myxomatosis”—a form of rabbit disease—is the title of one (dance) song on Hail to the Thief). But Radiohead, for all their PPE readings, are hugely less pretentious than Sting, who cannot stop praising himself for reading Lolita, or even Bono, for all his good intentions (indeed, some have argued that the intentions—to deliver the world on Judgement Day—are the problem).

Yorke studs the vocals with disarticulated vocal units, true music, virtually plainsong. Sometimes he communicates with words, sometimes with vocal effect alone. This type of modesty is worthy of some contemplation. (The track “Treefingers” is even instrumental.) Yorke develops a trend reminiscent of one Kurt Cobain revived from authentic punk: sing the lyrics with such utter passion, that they become indecipherable. Sure, something is lost (the explicit verbal text), but there is no denying something is gained when the human voice screams, wails and cries in a palette of colours almost unknown outside a locked unit.

Significantly, Yorke, who fussily oversees the production of beautiful CD booklets of original art for each album, has not reproduced Kid A‘s lyrics, having grown frustrated with verses being studied in isolation from the total sound. But what about a rare, crystal-clear line in “How to disappear completely” like “float down the Liffey”? That’s not just any old river: that’s Joycean territory you’ve dived into.

“There are two colours in my head/ what was it that you tried to say?” (from “Everything in its Right Place”) captures in a mere couplet what it took U2 an entire album (Zooropa) to communicate: the simple inability to hear a single meaningful thing in the babble and Babel of multichannel, surround sound culture. U2’s title song “Zooropa” contains some of its finest lyrics: “I hear voices, ridiculous voices/ Out in the slipstream/ Let’s go, let’s go overground/ Take your head out of the mud baby.”

Beyond immediately calling to mind a Rothko or Barnett Newman, the listener understands that the two colours either clash violently or can scarcely be distinguished, and the mental gymnastics instantly kick in. Yorke is very consciously twisting the radio knobs in your head, as a technician of synaesthesia.

Instead of an unambiguous forward move in a rock vein, which much of the industry had expected, Radiohead opted for an very ambitious lateral move into a form of electronica sometimes denigrated as esoterica. Kid A refused to function as OK Computer Redux. This decision did not generate universal praise; many critics saw a dodge or a stumble, and longstanding (and accurate) rumours of Yorke’s writer’s block and excruciatingly slow recording sessions in Paris, Copenhagen and the UK did not bode well for the release. Radiohead seemed ready to lose their mass audience fast upon assembling it with OK Computer (1997).

Thom Yorke is said to have initially stumped (and frightened) some members his four-guitar, one drum band with an abrupt fascination with electronica like Aphex Twin and Autechre (whom Yorke name-checks in every interview), causing the other members to reconsider their potential input with Kid A. Lead guitarist Johnny Greenwood is another incessant experimentalist, responsible here for instruments as diverse as the theremin and the Ondes Martenot. Production took a queer turn for a rock band. The title song “Kid A” would emerge from a computer program Yorke wrote. “Everything in its Right Place” would employ a 10/4 time signature. Not every player would play on each song. Some contributions were silent.

Titles like “Treefingers” and “Idioteque” are initially fearsome, bringing to mind spookily incoherent experimental music. But “The National Anthem” explodes into throbbing bass and horns in a kind of Merz-jazz, a caterwaul and feedback rapture.

Radiohead got their dance sound and bent their mental universe around it. “The National Anthem” has such a heavy, superb beat while voicing such bleakness that it might be best to dance to it in ESL. As music to crash your car to, however, that and “Idioteque” can’t be beat. Something to say for the group that produced the miracle of “Airbag” as the debut of the violently brilliant OK Computer, only one album before.

Tags: Bono, Johnny Greenwood, Kid A, Kurt Cobain, Nigel Godrich, Nirvana, OK Computer, punk, Radiohead, Thom Yorke, U2

This is a provocative review. I have a different tack on this and Radiohead’s 2 other main albums of OK Computer and The Bends. That’s all you really need to have. In any event I like the depth that you plumb on how you view this record.

I like their politics or possibly Thom Yorke’s politics as I consider Radiohead to be more of his project (realizing that he actually has solo work too). The British have a certain way of commenting on social justice inside the context of the industrialized and post-industrialized world at-large. What I mean by this is political philosophies of British punk bands like The Clash, The Mekons, and Gang of Four really know how to represent the lower middle-class ennui and hopelessness that for some really weird reason never translates to American politics.

I feel that Radiohead portrays those same kind of politics in their lyrics. However, as a child of both prog rock and punk rock, for me Radiohead is the perfect band combining all the elements I love about prog rock bands of the early 70s such as Yes, Jethro Tull, Genesis etc. with the political unrest that I feel so throuroughly in the bands aforementioned punk bands. Also, the never degenerate into overblown aimless noodlings as some of those bands do. Which I guess is why you get records like Kid A or OK Computer. And by the way I thought you were dead on in your analysis of ‘Kid A refusing to function as OK Computer Redux’ because it certainly didn’t. They are seperate and distinct albums. So really I am not sure that I am commenting here on Radiohead the band or Radiohead’s album Kid A.

Fascinating, Tim! Your review is better than mine, I think. I suspect the politicized apathy you identify is so much better articulated in the UK because they have a class system which they freely acknowledge exists. The US also has a rigid class system, but it refuses to acknowledge it exists as this flies in the face of the American Dream.

Class system exactly: I had thought that and was going to write that down above but forgot to. Thanks for articulating that. In the States, a class system exists, but because the country is so young, the middle-class actually still have a small amount of hope. They have not figured out that they are just tools of consumer culture cradle to grave, sperm to worm.

I also think there is an air of The Royals somehow being entitled without it being deserved. This somehow contributes to that class system ennui. I mean I certainly feel it here. British punk rock is what helped me kind of figure out some of my political philosophy.

One band out of the States called Mission of Burma has the identical political philosophy of the British punk bands. They capture that class system ennui pretty perfectly too. Good stuff. Atonal. Hard-edged. Drug-Fueled. Miserable.

Wow, loved your review.

13 of 13 readers found this review helpful on Amazon.com