No Country for Old Men

Directed by Ethan Coen and Joel Coen

Starring Tommy Lee Jones, Josh Brolin, Javier Bardem

2007

I defy you to keep easy track of the kills made by Anton Chigurh. His first, with perfect symbolism for a novel and film about law and order and crime and chaos, is of a silly young deputy in a jail where Chigurh is handcuffed. He gets the cuffs around the young man’s neck, and then it is just the work of holding on as the deputy thrashes and thrashes. Chigurh’s eyes are bulging, and the deputy’s death rattle provokes an obscene swoon from the killer. This may be the film’s only vulgarity.

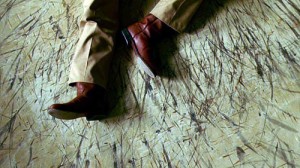

It put me in mind of a documentary I saw about tarantulas. One couple, known honest to god as Tucson Blondes, rolled around and kicked with all sixteen legs at each other and the ground when a gentleman came calling and the lady wasn’t in the mood. The male didn’t make it; the female was largely uninjured. I bet the wild action painting the Coen Brothers organized with black shoe polish and legs trying to get a purchase on the ground matched the markings scratched into the dirt by those frantic spiders.

The West Texas land gives of itself almost nothing, but things are perched on it like rocks and soil hostile to life: dirt more like it. It does a good impression of the middle of nowhere. There is a kind of beauty for those passing through. Staying means death. In his introduction, hunter Llewellyn Moss (played by Josh Brolin) takes aim at an antelope and misses. And there we have it. A hunter: but will he prove good enough? G.W. had the iconography of the cowboy more or less right, as did Reagan, but you see immediately that the real thing is as hard, spare and grim as Cormac McCarthy’s writing. The men’s faces are masculine, hard, with unnecessarily thick moustaches. Their bodies are sinewy, thinned, realistic, without decorative musculature or even decorative asses. They are masters at tracking. Every man in the film can read the ground, and does routinely like we read a clock. It is all nature, no culture, in the sense that the nature/culture divide intends.

The Coen Brothers give themselves the shortest of leashes. There are no Coens, in a recognizable sense: there is almost no sign of the scallywags of Fargo (1996) or Raising Arizona (1987). This is intense humility, a very profound respect for novelist McCarthy. There is virtually no humour in this film, which must have been downright painful, like suppressing the giggles outside the principal’s office. The story travels quickly, like its characters, and the movements over geographical distances unfold effortlessly. No Country has virtually no technical faults. It won four Oscars, each perfectly chosen: Best Direction; Best Screenplay Adaptation; Best Supporting Actor (Javier Bardem) and, of course, Best Film.

Llewellyn Moss, who found and stole an already stolen satchel containing $2M of drug money, walks into a peaceful little hotel. In front of the check-in desk, a little cat drinks milk out of a bowl. All the cat has to do is exist and your fear spikes. A little while later, Moss finds the pussycat drinking spilled milk off the floor. Whew: could have been a lot worse. In fact, it was, for the check-in clerk.

The novel and the film make a brilliant decision in talking so little about Chigur (played by Spanish actor Javier Bardem), providing virtually no explanation for his origins or behaviour. A man hired to kill Chigurh (Woody Harrelson) is asked a couple of questions about his target (they are acquaintances) before being sent on his journey. The enjoyable smartass answer: “[Is he] dangerous in comparison to what? The bubonic plague?” Though Harrelson was once Chigurh’s contemporary, we know nothing of their falling out. In fact, in the novel, Chigurh eventually returns the money to the drug lords in exchange for future business. But you get the sense that it kind of isn’t really about the money. He has no sex, no relationships of any kind, and no desire to form them. Chigurh kills because he is so good at it, because it comes naturally, because it is an extension of who he is: the same reason why a painter paints or a runner runs.

Instead of background, we get beautiful folklore. A dying Mexican Moss finds in a truck packed with black tar heroin asks for water and gets none. He then asks only that the truck door be closed. He moans about “lobos”. With too much confidence, Moss says “there ain’t no lobos” and leaves the door open. The lobos-serial killer link hasn’t fit so well, and come as such an overt warning, since Jonathan Harker pulled up to Castle Dracula in Transylvania. Sure enough, a “lobo” will find the Mexican before the evening is out.

Chigurh’s haircut is something to be seen. It is a pageboy, belonging to a young girl going through a plain stage. She will look back at childhood photos with resentment and horror as something that explains instantly years of needless bullying. A haircut so grotesque would seem to constitute a vulnerability on Chigurh’s part, but it doesn’t. You don’t mock the big man with the alien eyes and the cattle gun for his little girl hairdo. It is perhaps the most frightening thing about him. Only an outlaw would style his hair this way every morning, neatly as a psychopath, and go about his business as an assassin. It takes a man to style himself like a seven-year-old girl.

He is foreign, but nonspecifically so. (Bardem is Spanish, but Chigurh presents himself to victims as nothing in particular: not a Mexican, but rather a something in a set of one. He is someone of a kind you’ve never met before: your killer.) His name is a pun. Texans think his name is “Sugar”, but it is actually pronounced “chigger” after the insect that buries itself in the flesh.

Chigurh, passing under a covered bridge, spots a dozing bird perched harmlessly on a scaffold. Smoothly, instantly, Chigurh draws his gun and fires. The bird escapes, but Chigurh’s whiplash throwback to the triad of sociopathy (here, killing animals) confirms any lingering suspicion about what type of creature he is.

Naturalist Gordon Grice’s exquisite book on insect and reptile predation, The Red Hourglass, could be a companion volume for No Country. Grice remarks that there is “no unambiguous benefit” to super-sized toxins, as the black widow possesses, which can kill animals infinitely larger than the widow and can be of no possible use-value to it. He talks of “flowers of natural evil”.

We want the world to be an ordered room, but in a corner of that room there hangs an untidy web. Here the analytical mind finds an irreducible mystery, a motiveless evil in nature; and the scientist’s vision of evil comes to match the vision of a God-fearing country woman with a ten-foot pole. No idea of the cosmos as elegant design accounts for the widow. No idea of a benevolent God can be completely comfortable in a widow’s world. She hangs in her web, that marvel of design, and defies teleology. ((Gordon Grice, The Red Hourglass: Lives of the Predators. (New York: Delacourte Press, 1998), pp.58-59.))

Like Grice’s Black widow, or the absurdly deadly Sydney funnel web spider, or even the black mamba, Chigurh will kill just to pass the time of day. Sheriff Bell calls him a kind of “ghost” because he leaves no living witnesses. But like many venomous predators, Chigurh can choose between wet and dry bites. Most venomous predators will choose a dry bite to preserve venom, if they can. Chigurh is the reverse: he’ll blow a hole through your head as soon as look at you, but once in a while, for no special reason, he will deliver a dry bite. In Chigurh’s case, that means flipping a coin and demanding that the victim call it to save her own life. Like a mathematician, Chigurh is fascinated by chance, and discourses on it in the novel.

But like all the gratuitous predators in the world, Chigurh will eventually provoke attempts at vengeance, or at least containment. Would you leave a King Cobra in your garage? Police follow Chigurh, even at a polite distance, as do other criminals. Is he vulnerable?

Chigurh is something of a natural fascination. He’s an apex predator, something to see, like a lion in the savannah or a great white shark in the ocean. As is often remarked, predation is an arms race, using factors like speed, more powerful venom, more convincing camouflage. We have an arms race here, involving another professional hit man (Woody Harrelson), a sheriff (Tommy Lee Jones) and a thief (Josh Brolin).

Chigurh is a creature of nature: God’s creature, like a lizard or a coyote or a Tucson Blonde tarantula. He does not speak enough to acquire the shadings and cultural grandeur of Hannibal Lecter, who uses civilization against his victims, who become his students at the same time as they are preyed upon. Occasionally, they are lectured to death. (This happened, for example, to the late Commendatore Rinaldo Pazzi of the Questura in Hannibal.) We don’t begin to get to know Chigurh. But Cormac McCarthy’s Anton Chigurh is deeply honest in construction, and is reminiscent of anti-hero of the most authentic Lecter book, The Silence of the Lambs (1988). Lecter, a committed atheist who believes with devotion in beauty, says: “Typhoid and swans – it all comes from the same place.” This is a brutally difficult stance for the author to maintain.

Thomas Harris has Lecter knowledgably reject all psychology and much of human philosophy when he says: “Nothing made me happen. I happened.” In time, Harris would lose the faith required to maintain this position—-that Lecter was simply a variant of nature, a black swan—-when he wrote his weakest book, the Making of Hannibal Lecter, called Hannibal Rising (2007). An abused orphan has a quasi-incestuous relationship with a beautiful aunt, etc., etc., and kills only to avenge his family, and not for recreation, unlike the adult Hannibal. This is hard to read; Hannibal Lecter was a free man behind prison walls, free to think, to fantasize, and to own up to any crime he wanted. Young Hannibal is shackled by the memories of a dead family and the grind of medical school.

Unlike Lecter, Chigurh doesn’t do anything with the bodies. He doesn’t desecrate them or even observe them. He is often in movement by the time they hit the floor. The deaths take only half a second, and it is possible that the victims, like cows, do not even suffer, with their instantaneous loss of their frontal lobes. Along with his freaky hairstyle, Chigurh has a freaky weapon: an airgun for cattle that fires a six inch metal rod between their eyes that then instantly retracts. It is crazily efficient. He erases nearly every witness as he goes. He doesn’t fuss with fingerprints or forensics, but he erases human memories as they are formed. There is surely a comment here on the anonymity of modern personal interactions: a corollary that says that everyone is disposable. To meet someone is to forget them.

Chigurh does not even get angry when he is thwarted for time to time on his mission, any more than a force of nature would have feelings about anyone’s destruction or the time of its arrival. He knows he is inevitable, and says so. He can be wounded, even seriously, but like an evil Boy Scout, he engineers his own rescue. He is philosophical, like the story’s failed referee, Sheriff Bell.

Chigurh almost meets his match with a marvelous secretarial gorgon who oversees the group of trailers in which Moss lives. This is the sort of monster who earns less than $20K a year and could put the President of the United States in his place, in broken English no less. She’s a manifestation of pure bad attitude and an intention to thwart any activity. Chigurh asks where Moss is. The obese woman, with that loose, all-American wattle, says that she can’t provide no information. Chigurh repeats the question without so much as a change in inflection. The secretary is getting annoyed and repeats that she cannot give out no information. Chigurh goes for a third time, with perfect uninflected repetition. The secretary is righteous enough (“no information”) to be unafraid of the bizarre stranger, and the flushing of a nearby toilet is a fitting mode of salvation for her, when Chigurh looks at her a last time and then slides out the door. How many Chigurhs do any of us ever pass, saved by the flush of a toilet, never to know how our lives came down to a coin toss?

Sheriff Bell is always at the right place at the wrong time, staying calm, counting the dead, more like a coroner than an effective crime fighter. He misses Chigurh by such a fleeting distance that he spots a sweating quart of milk on a table which the killer which has left behind. Sheriff Bell takes Chigurh’s place on the couch and drinks deeply from the same milk bottle, as if tasting something touched by this alien species, tasting Chigurh himself. Another method of tracking.

Sheriff Bell is given time throughout the film to pause and comment on the action that he cannot begin to control with short Texan sentences like something whittled white and beautiful. “I always thought when I got older God would sort of come into my life in some way,” says the Sheriff. You hope for him. “He didn’t,” is the follow-up, brave and mournful.

A wonderful scene unfolds when Sheriff Bell has coffee with the Sheriff of El Paso, where a Chigurh bloodbath has just gone down. Both men, both in their 60s, realize they are no match for the metastasis of American violence. The Sheriff of El Paso has begun to crack under the strain: “If you had told me twenty years ago that the children in our Texas towns would have green hair and bones in their noses, I just flat out wouldn’t have believed you.”

“Signs and wonders”, says Sheriff Bell, politely and healthily.

Tags: Academy Awards, Anton Chigurh, Carla Jean Moss, Cormac McCarthy, Ethan Coen, Gordon Grice, great white shark, Hannibal, Hannibal Lecter, Hannibal Rising, Joel Coen, Josh Brolin, Llewelleyn Moss, orca, predation, Sheriff Ed Tom Bell, Texas, The Silence of the Lambs, Thomas Harris, Tommy Lee Jones

Fantastic piece of writing. A couple of quick thoughts:

1) The bit about Chigurh’s hair – especially “It takes a man to style himself like a seven-year-old girl”, which is one of the most quotable lines i’ve ever read – is keen. It’s not unlike the cliche that art can be so bad that it’s good: Chigurh’s appearance is so unassuming, so very much *not* what we expect of a killing machine, that he becomes even more disturbing for having such an appearance.

2) The point about Lecter is good, too: evil, in a literary sense, is at its most frightening when it is akin to nature. Heroes require psychology and anti-heroes need, at the very least, a backstory that recuperates their violence. But villains are undermined and weighed down when their writers try to humanize them. (I’m thinking, for instance, of the difference between Lex Luthor – purely villainous, purely narcissistic – versus Magneto, whose backstory makes it impossible to view him unambiguously as a villain.)

Of course, I wonder if Harris changed things for the same reason that I have political objections to this kind of evil, persuasive as it may be – Chigurh and Lecter cannot be human. The problem is when this literary evil is expropriated to real life – when it gets applied to The Terrorists, for example, who are similarly spoken of as if they, too, were born to poison and are not the products of international and domestic politics, to say nothing of their socio-cultural place of origin. Because it is seductive, and easy, to believe that Osama bin Laden or Adolf Hitler or Hannibal Lecter were born as black widows.

And, conversely, it is unsatisfying on a literary level to have that killer-streak explained away. For example: Family Guy has this bit where we’re shown Hitler’s origin – he’s at the beach trying to pick up girls, and a Jewish strong man kicks sand at him and steals them from Hitler. It’s a particularly absurd origin story, of sorts, but makes a good point – every origin story for an ‘evil’ person, short of showing them emerging from hell itself, will be too banal, too mundane, and wholly disappointing. Better, as art, to let it remain ultimately mysterious and mystifying. Except that what’s good for art, in this instance, encourages ignorance of the actual conditions that lead to the creation of a Hitler.

I don’t have an answer or a resolution – I like that ambiguity in the art, just as I like that sociological aspect in my politics, and the two will be forever in tension – but I just wanted to write it out.

I misremembered the Family Guy clip – I found it, though, and posted it to my blog, along with a version of this response.

Wednesday, August 18, 2010

Representing ‘Evil’

Erin has written this fantastic post on, well, evil in films that ties together Chigurh (from No Country for Old Men), Hannibal Lecter, and black widow spiders. You should read it because, like I said, it’s fantastic. If the line “It takes a man to style himself like a seven-year-old girl” doesn’t have you wanting to read it right now, then nothing will.

I wrote a comment on Erin’s blog, and wanted to repeat myself here, just a little bit. In comparing these three, Erin labels them “creature[s] of nature”, though she rightly qualifies and complicates Hannibal a bit – but, at least in Silence of the Lambs, Hannibal has no history, and this is just as good as being a creature purely of nature. She also notes that it would be unsatisfying to ‘explain’ Chigurh, just as the origin provided in the novels set chronologically before Silence of the Lambs only seem to damage Hannibal’s character. It seems as if art’s most persuasive and frightening villains are diminished in being understandable – in being made human.

For instance, from the pilot of Family Guy, we get this ‘origin’ for Adolf Hitler:

It’s particularly absurd, but I think it manages to express, in 10 seconds, what was wrong-headed about trying to ‘explain’ where Hannibal Lecter comes from. No matter the explanation, the origin will always be too banal and too mundane, even too relatable or too sympathetic – nothing short of showing Hitler emerging from Hell itself will be satisfying, because we don’t want our villains to be explicable – we want them to be exceptional.

And this expectation and satisfaction is horribly problematic. Because this is exactly how politicians and pundits get away with constructing The Terrorists as evil entities that exist somehow outside politics and history. Because our art teaches us that we shouldn’t want to know where evil comes from, and that in any case it emerges directly from nature and is merely acting on that nature, like a black widow or a tornado. We don’t need to know why a suicide bomber is a suicide bomber anymore than we need to know why Chigurh kills – they just do.

I don’t remember where or when, but Geoff once made the comment on his blog that there was something in the hypervisible misogynistic violence of the Sin City film that he found appealing, and it was a bit troubling because it was so gratifying as a film experience and obviously disgusting as a gender politics. And I feel the same sort of unresolvable ambivalence about these evil characters in No Country for Old Men and Silence of the Lambs.

Labels: films, masculinity, television

//http://neilshyminsky.blogspot.com/

posted by neilshyminsky @ 2:00 PM 0 Comments

I really enjoyed this post. I’ve never really thought about it before, but pretty much across the board, all evil origin stories kind of suck.

In an interview with Jonathan Nolan, he discusses writing the screenplay for The Dark Knight, and how he really wanted to approach the Joker as more of an elemental force, as opposed to a person with a history. When we first see Heath Ledger standing on a street corner, his back turned to the audience, it’s as if he was conjured from thin air. It makes the character so much more compelling and frightening.

Is it simply a matter of “the unknown” is always more interesting, and often times scary, than actually understanding what evil is? Even thinking back to the origins of comic book villains, I’m hard pressed to find one that actually enhances the evil aura of a villain, rather than simply muddling it. Generally, most origins of villains seem to evoke sympathy from the audience: Darth Vader was a kid who was taken away from his mother, Mike Meyers was…also a kid that was taken away from his mother. By telling us this, it doesn’t really add anything to these villains it mostly just takes away.

Sorry if this post rambles a bit too much. Again, really really enjoyed reading this piece.

James said…

Wow, Erin’s blog is fantastic: bookmarked (in my brain).

Great piece, Erin, but about two films I couldn’t watch! And think you’re right about evil – if there’s a cause, there’s an explanation, and I don’t believe there is one.

Excellent, as always. What do you think overriding themes of movie are? Could it be nothing at all? Or?… I sense from this that it’s weirdly comic. Is it?

Haven’t seen the film, but this makes me want to. YOU should be doing the New Yorker reviews…

Yes, there are elements of potential weird comedy, and a cute scene when the Sheriff visits a guy with a zillion cats who says that “some of them are half-wild and the rest of them are just outlaws”. But people are so degraded by the flip-a-coin aspect of life and death that one character refuses to participate and is simply killed outright. In the book, it is even worse, because the character is made to agree to Chigurh’s coin-toss philosophy while, of course, sobbing. The next line in the novel is: “and then he shot her.” It’s just sickening. Beyond the atmosphere of menace, there are sad moments, like when the Sheriff admits he never found religion.

If I had to write in a more serious way on this subject (and thank god I don’t!), I am interested in what Chigurh says to one victim (who does win the coin toss and escapes) about how a coin has been “traveling” toward him for 22 years since its minting and that Chigurh in turn has been traveling toward him for a long time. Likewise, he says the man has been “putting [something unidentified] up” his whole life, and that thing has now become what will be won or lost in the bet (the man’s life: but he doesn’t know it).

This actually reminds me a lot of the late medieval/Northern Renaissance obsession with the figure of Death who was creepy looking (decaying) and used a strange weapon (sickle). And the freaky hairstyle wasn’t totally arbitrary: the Coens came up with it independent of the novel, based on an image of a 19th century American brothel patron. Does that mean that Chigurh is immortal, in a way, with an antique method of styling himself, like a Dracula figure? Like Death himself is immortal? There is also a hint at the great leveling of Death (and the dance of death), when the freaked-out El Paso Sheriff (on the border with the inconceivable Ciudad Juarez, a factory of corpses) observes that Chigurh killed a desk-clerk at a hotel and then a retired Army Colonel.

But certainly, a “serial” killer (not really, here: more just a hit man gone berserk) has to have a “gimmick” to be truly terrifying, at least for the public. Chigurh has the hair, the coin and the airgun.

Thanks so much, Erin. I loved both posts.

You have this way of capturing the essence of possibly deplorable characters in a very clinical and objective way. I too did not see the Chigger (ha!) character as an evil character so much as a “bad guy” but as you insinuate a person who finds it necessary to express himself or as a person who is good at a particular vocation. Money ISN’T the goal. If you have seen the latest installment of the “Dark Knight”, Heath Ledger’s Joker is another excellent example of money not being the impulse. The impulse is to ‘do a good job’ with whatever it is you have to do a good job with AND do it well. I see nothing wrong with that on a purely objective level.